Whitepapers

White Paper: The Five A's of Cannabinoid Skincare

Written by Alexia BlakeHead of Research & Product Development

In the context of personal care and beauty, skin is often overlooked as the body’s largest organ. Rather than just serving as a blank canvas to treat, paint, alter and otherwise manipulate, it is easy to forget that skin serves a multitude of other (and perhaps more essential) purposes 1,2.

First and foremost, skin acts as a protective barrier between our bodies and the outside world of external aggressors, such as bacterial pathogens, pollutants, and radiation. It also serves as an interface responsible for temperature regulation and detection of sensorial triggers such as heat, cold, pressure and pain. Lastly, skin acts as a filter for absorption and excretion while also preventing excessive water loss from our bodies.

Amidst these many responsibilities, skin is often under constant assault – not just from the outside world but also from within. Environmental assailants such as UV radiation, chemical irritants, pollutants, and bacterial pathogens constantly attack our skin, challenging its ability to function as an impenetrable barrier while also triggering a constant process of repair and renewal. Internal stressors such as cytotoxic cells, cellular debris and everchanging physiological conditions impacted by genetics, stress, sleep, and diet place similar demands on skin 3.

In seemingly all cases, skin is in a defensive mode fighting off impending damage. This often requires support from the body’s immune system, which like skin, may wane in its strength and resiliency over time 4,5. When the skin and immune system become impaired, people may experience an array of negative outcomes including irritations and sensitivity, breakouts, premature ageing, and the development of dermatological conditions such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis 6,7. Solutions designed to keep skin healthy should therefore aim to address the varied root causes of skin damage, rather than focus solely on cosmetic outcomes.

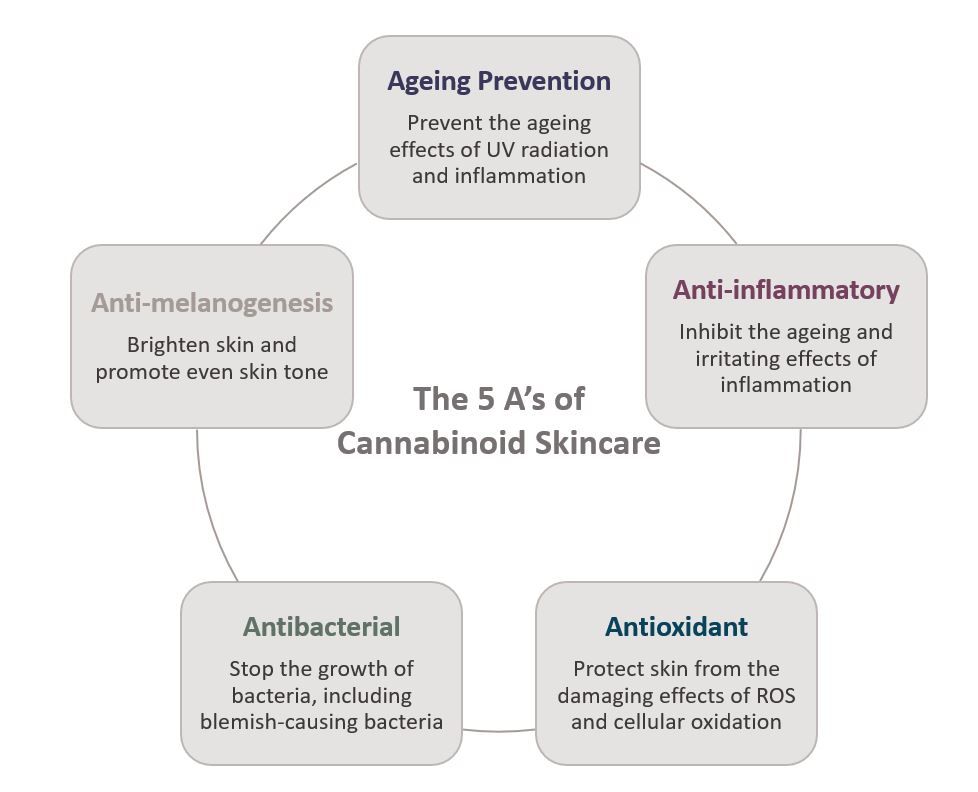

To this end, the possibilities of cannabinoids for skin health are immense. Despite the rising popularity of cannabinoids such as CBD for promoting wellness-related outcomes associated with improved sleep, mood and pain, a growing body of robust scientific evidence is also revealing that cannabinoids such as CBD and, in particular CBG, provide a multitude of benefits for skin that Cellular Goods refers to as the 5 A’s of Cannabinoid Skincare.

It is these benefits that form the basis from which cannabinoids such as CBG and CBD can keep skin healthy, smooth, firm and radiant. From clear and calm skin to ageing prevention, cannabinoids are powerhouse ingredients that present a new frontier for skincare.

However, harnessing their full potential for maximum benefit requires a sound understanding of their unique properties. In this whitepaper, the multifaceted benefits of cannabinoids, namely CBG and CBD, are summarised with the intent of providing consumers and formulators alike with an appreciation for the colourful spectrum of benefits these fascinating ingredients can confer to skincare applications, particularly when compared to traditional skincare ingredient such as retinoids, Vitamin C, and exfoliating acids, which are often limited by their irritation potential and risk of photosensitivity.

As safe, effective and well tolerated ingredients, cannabinoids undoubtedly present skincare solutions of the future.

Table of Contents

The 5 A's of Cannabinoid Skincare

Cannabinoids are powerhouse ingredients that provide a multitude of benefits for skincare applications. These benefits, collectively referred to as The 5 A’s of Cannabinoid Skincare, are the means through which cannabinoids such as CBG and CBD can keep skin healthy, smooth, firm and radiant:

- Ageing Prevention – mitigate the ageing effects of UV radiation (aka photoaging) and inflammation (aka inflammaging)

- Anti-inflammatory – inhibit inflammation as a leading cause of skin ageing as well as local irritation caused by a range of stimuli that contributes to redness, dryness and irritation

- Antioxidant – protect skin from the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cellular oxidation

- Antibacterial – inhibit the growth of bacteria, including blemish-causing bacteria

- Anti-melanogenesis – prevent excessive melanin production to promote skin brightening and even skin tone

These benefits are underscored by the excellent tolerability of cannabinoids, making them suitable for any skin type. The same cannot be said for other conventional ingredients that consumers typically turn to for support with anti-ageing, blemishes, and skin tone related concerns, such as such as retinoids, exfoliating acids, Vitamin C, kojic acid, or benzoyl peroxide, as these ingredients are often limited by their irritation potential and (in some cases) risk of photosensitivity.

Simply put, these traditional skincare ingredients fall short of cannabinoids which provide a wider range of skincare benefit without the risk of irritation. Cannabinoids such as CBG and CBD clearly represent a new frontier of effective, safe and tolerable ingredients that can elevate any robust skincare routine.

The First A – Ageing Prevention

Popular anti-ageing actives including Vitamin C, retinoids and exfoliating acids, though effective are characterised by a high irritation potential. This chapter explores the impactful role that CBG and CBD can play in keeping even sensitive skin healthy and visibly rejuvenated by fighting inflammaging and UV-damage, two leading causes of skin ageing.

A recent whitepaper by Cellular Goods detailed the ageing prevention benefits of CBG and CBD for skincare 8. Specifically, the combined anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of CBG and CBD enables these compounds to protect skin from the well-established ageing effects of inflammation and UV-damage, both of which are key drivers behind visible skin ageing.

The benefits of cannabinoids for ageing prevention are differentiated from the existing catalogue of anti-ageing ingredients such as Vitamin C, retinoids and exfoliating acids in several ways. First and foremost, the use of these conventional ingredients is often limited by their irritation potential and risk of photosensitivity. This presents a challenge for consumers, especially those with sensitive skin, who must make a trade-off between minimising the concentration or frequency of use of these ingredients to avoid irritation in the form of redness, dryness and peeling in exchange for reduced or delayed efficacy. Fortunately, this trade-off is not required for cannabinoids due to their tolerability and potent anti-inflammatory properties.

Secondly, these ingredients are often positioned as reactive solutions to address existing signs of skin ageing. This is in part due to their different mechanisms of action when compared to CBG and CBD, specifically in the context of collagen synthesis and exfoliation. While these benefits are undoubtedly desirable, it is worth noting that cannabinoids present a proactive solution to skin ageing thanks to their protective properties, and therefore complement these other ingredients.

Cellular Goods successfully confirmed these benefits in an in-vivo study involving their Rejuvenating Face Serum. In their study involving 166 female participants with a range of Fitzpatrick skin types (I - VI), participants reported that skin was visibly rejuvenated, appeared healthier, more radiant, and smoother after 4 weeks of use (Table 1). Additionally, the Rejuvenating Face Serum was determined to be suitable for sensitive skin, with results from the in-vivo study confirming the tolerability of this product.

Table 1: Summary of key results following a 4-week study involving 166 female participants to assess the ageing prevention benefits of Cellular Goods’ Rejuvenating Face Serum.

These results provide a first corroboration of the ageing prevention benefits of CBG. Thanks to the combined anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of CBG against UV-induced damage and inflammation as two key factors behind visible skin ageing, this cannabinoid presents an effective and well-tolerated solution to keeping skin healthy.

These results have formed the bases of the new Rejuvenating Range from Cellular Goods. These breakthrough products contain a proprietary blend of CBG, CBD and other active skincare ingredients to fight inflammaging and UV-damage, leaving skin healthy and looking its best. These are the ageing prevention solutions of the future providing visibly smoother, firmer and radiant skin in just 4 weeks.

The Second A – Anti-inflammatory

Inflammation is a leading cause of skin ageing. This chapter examines findings that reveal CBG and CBD’s significant capacity to prevent inflammation caused by common stimuli, including UV radiation and bacterial pathogens, in a manner that is more effective than Vitamin C.

Inflammation is caused by a range of external factors, including UV exposure, bacterial pathogens, chemical irritants, and allergens. In some cases, inflammation is part of our body’s natural immune response, participating in complex signalling mechanisms to protect against further injury and infection 9. In other cases, inflammation plays a critical role in the healing process, working to modulate different stages of recovery and repair 10,11.

However, a growing body of evidence is revealing that chronic inflammation may in fact accelerate ageing processes. This process, recently coined “inflammaging”, involves cumulative tissue damage and was first discussed in the context of ageing-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, arthritis, diabetes, atherosclerosis and macular degeneration 11-14. More recently, it has become apparent that inflammaging is in fact a determining (and perhaps underestimated) factor of skin ageing as well.

A recent review of the current science of inflammation and skin ageing presented that aged skin can be characterised by three main traits: an accumulation of senescent (aged) cells, a disorganised extracellular matrix (ECM) structure, and an increase in immune cells with impaired functionality 3. Inflammation is a driver of all these changes and can be caused by internal factors such as diet and stress, or by external factors like UV radiation and pollution. To make matters more complicated, senescent cells with impaired functionality, ECM breakdown and dysregulated immune activity can contribute to inflammation, creating a cyclical relationship between inflammation and ageing that worsens over time (Figure 2). This means that inflammation can not only accelerate the onset of ageing skin, but also exacerbate ageing processes once they have started.

Figure 2: Current understanding of the process and impact of inflammaging on skin ageing. Inflammation can be caused by various internal and external factors, causing a cyclical and compounding cascade of effects related to ECM breakdown associated with collagen and elastin loss, impaired immune function and an increase in pro-inflammatory senescent cells 3,15.

In accordance with this understanding of inflammation-induced ageing, the authors defined inflammaging as chronic, low-level inflammation associated with ageing that is characterised by increasing levels of systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines, small proteins that are crucial in controlling the activity of other immune system cells and blood cells, and a marked shift towards cellular senescence. They demonstrated in their review how these changes are correlated with the hallmark signs of ageing skin, including a loss of elasticity, fine lines and wrinkles, an impaired barrier function, increased risk of skin infection and an impaired ability of skin to repair following injury or infection.

While the cumulative effects of inflammation on skin health and immunity are intriguing, it is also worth noting that inflammation may also present as an acute or short-term symptom. This is often the case with dermatological conditions such as contact dermatitis, which is defined as irritation to the skin caused upon contact with an allergen or irritant 16. UV radiation can also induce short-term inflammation by way of sunburns. Compounds with anti-inflammatory properties, such as cannabinoids like CBG and CBD, can therefore attenuate inflammation and, through extension, mitigate the effects of inflammation on skin barrier disruption, redness, irritation and premature ageing.

Where UV-induced inflammation is a driver of inflammaging, Willow Biosciences reported that pre-treatment of human dermal fibroblasts with CBG or CBD was more effective than ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) and preventing inflammation caused by UVA radiation 17. Interestingly, CBG was statistically (p<0.5) more effective than CBD at inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory marker interleukin-6 (IL-6). In a separate study, Willow Biosciences reported that CBG was twice as effective when compared to CBD at inhibiting the release of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a pro-inflammatory regulator inflammation and immune activity, from normal human epidermal keratinocytes (keratinocytes represent the major cell type of the epidermis, the outermost of the layers of the skin, making up about 90 percent of the cells there) exposed to UVB radiation 17. These results align with those previously reported by Cellular Goods, which detailed that pre-treatment of CBG, CBD and specific combinations of the two cannabinoids was effective for inhibiting inflammation as measured by pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-8 (IL-8) release following UVB exposure in 3D cultured human epidermal skin tissues 8.

Willow also reported that CBG was more effective than CBD by a 5-fold difference at preventing inflammation caused by the chemical irritant tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate (TPA) in normal human epidermal keratinocytes 17. These results were confirmed during a single-blind placebo-controlled clinical study involving 20 healthy volunteers which assessed the ability of 0.1% CBG (applied in a serum matrix) to prevent inflammation and barrier damage caused by the chemical irritant sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) as an inducer of contact dermatitis 17. There was a statistically significant p<0.05) lower level of transepidermal water loss (TEWL) for CBG-treated sites compared to untreated or placebo sites, as well as less inflammation and redness after 48 hours. This trend continued over 2 weeks of application, with CBG-treated sites returning to baseline levels as measured using a visual scale for erythema.

These results provide compelling evidence of the anti-inflammatory benefits of CBG and CBD. Given the complex interplay between inflammaging and ageing, CBG in particular can provide a range of modalities to prevent inflammation caused by various factors, and in doing so protect skin from age-inducing aggressors. In fact, the anti-inflammatory properties of cannabinoids are so powerful that researchers are exploring the benefits of these compounds for a range of inflammatory dermatological conditions, such as eczema and psoriasis 18,19,20.

The Third A – Antioxidant

A growing body of research has demonstrated that CBG and CBD, are equally if not more effective than the common antioxidant Vitamin C at protecting skin from the harmful effects of UV exposure and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that are ubiquitous in ageing, photoaging and inflammation. This chapter explores the meaningfully positive implications of cannabinoids’ antioxidant properties for skincare and beyond.

The term "antioxidant" generally describes a compound that inhibits oxidation. Oxidation is technically defined as a process during which a molecule loses an electron, and more contextually is a process that can lead to degradation of active ingredients, such as Vitamin C. This loss of electrons is commonly driven by reactive compounds known as free radicals, which include reactive oxygen species (ROS). These are highly reactive oxygen-containing molecules that can accumulate in cells and disrupt the structure and normal functioning of lipids, proteins, and DNA 21.

Interestingly, our bodies produce low levels of ROS as by-products of various biological processes 22. For this reason, the human body possesses a natural antioxidant defence system that relies on a series of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants to interrupt the destructive cascade of events caused by ROS and protect cells from the damage they can cause 23. However, an overaccumulation of ROS can overwhelm this innate antioxidant defence system, leading to a state known as oxidative stress. When this occurs, ROS become unstoppable and cause a series of deleterious effects ranging from cellular inflammation, apoptosis (cell death), impaired cellular signalling and even breakdown of the proteins and lipids in our skin 24. The negative impacts of oxidative stress are so far reaching that they have been linked to the aggravation of various skin diseases such as psoriasis, acne, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis and (of course) skin cancer 23,25.

Overtime, the damage caused at both a cellular and tissue level can impair the healthy functioning of skin while also leading to a loss of collagen and elastin 24,26. This cumulative damage has been shown to accelerate skin ageing, which manifests as rough skin, the formation of fine lines and wrinkles, a loss of elasticity, and uneven skin tone. Skin may also become drier and more sensitive as the composition of skin changes and the skin barrier becomes less effective at preventing water loss.

While our bodies produce some levels of ROS as a by-product of biological activities, the greater cause for concern is the creation of ROS caused by UV exposure. As detailed in a previous whitepaper by Cellular Goods, UV exposure is accountable for up to 80% of the signs of skin ageing. In addition to being a major source of ROS generation, UV exposure can accelerate ageing through a series of other mechanisms, many of which induce inflammation and structural or compositional changes to the skin, such as lipid peroxidation.

The use of antioxidants has therefore become common practice in skincare, as it has become well-established that these ingredients can neutralise ROS, thereby protecting skin from their damaging effects. Vitamin C has undoubtedly become the most popular antioxidant to this end, with many serums, creams and other treatments touting its anti-ageing benefits. However, emerging research has demonstrated that cannabinoids such as CBG and, to a lesser extent CBD, are equally if not more effective than Vitamin C at protecting skin from the ageing effects of UV exposure and ROS activity.

A recent study published by Willow Biosciences found that CBG and, to a lesser extent CBD, had higher antioxidant capacities than Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) and were consequentially more effective at preventing the formation of ROS within human dermal fibroblasts (p < 0.05) 17. Similarly, a separate study by Cellular Goods reported that both CBG and CBD were effective at preventing significant UVB-induced lipid peroxidation in 3D epidermal skin tissues, a known factor behind visible signs of skin ageing 8.

Taken together, these results indicate that cannabinoids such as CBG and CBD can mitigate the damage caused by ROS and UV exposure, equally and in some cases more effectively than Vitamin C, to maintain a healthy and functioning skin barrier and prevent premature signs of ageing. These findings also complement a growing body of medical evidence supporting the compelling antioxidant properties of cannabinoids which are relevant for a number of other research areas including cancer, neurological and cardiovascular research 27-29.

The Fourth A – Antibacterial

As many consumers will attest to, there is aclear need for non-irritating yet effective solutions for product formulas fighting acne. Owing to observed antibacterial and anti-bacterial properties, cannabinoids like CBG are extremely well positioned to tackle blemish-related concerns, not just in the world of skincare but also within clinical settings. This chapter dives into the importance of antibacterial actives in skincare and the data on how CBG is positioned to provide a number of antibacterial solutions.

Acne vulgaris is a dermatological condition affecting 9% of the global population 30. While acne most commonly presents during puberty, it is well established that acne may also occur during adulthood and menopause 31. As a result, experiencing troubles with acne is a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’ for many individuals. These troubles often extend well beyond the skin, leading to mental health issues related to depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem 32,33.

To make matters worse, the treatment of acne is complicated by the diverse range of individual factors contributing to the manifestation of this disease, including genetics, stress, diet and hormones 34,35. However, researchers have identified three mechanisms that consistently contribute to the formation of blemishes and can be targeted through various treatments: an overproduction of sebum (oil) by the sebaceous glands, impaired skin shedding (desquamation) coupled with excess production of keratin proteins (hyperkeratinisation), and an overgrowth of the gram-positive pathogen Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) 33,36,37.

There is a degree of interplay between these factors that makes the development of skin blemishes a compounding process. Specifically, an accumulation of waxy material comprising, sebum, keratin and dead skin cells can form “sebaceous filaments” that plug glands and follicles in the skin. Sebum is also consumed by C. acnes, fostering the overgrowth of this bacteria which releases pro-inflammatory compounds called “porphyrins” that trigger an immune response marked by further inflammation 33,38. This leads to the formation of inflammatory acne.

With this understanding, a range of prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) treatment options targeting specific factors of acne vulgaris’ pathogenesis have emerged. At the forefront of these options are retinoids, which as topical or oral therapies exert anti-inflammatory and comedolytic (anti-pore clogging) effects to reduce or prevent the formation of pimples 39,40. While effective, retinoids are infamous for their irritation potential, photosensitivity and contraindicated use during pregnancy due to the risk of birth defects 41,42. Alternatively, oral or topical antibiotics may also be used as prescription treatments to inhibit the growth and inflammation associated with C. acnes 43. However, growing concerns of antibiotic resistance coupled with the gastrointestinal impacts of long-term antibiotic consumption may render this treatment option less favourable. Instead, hormone regulators such as androgen-receptor blockers or oral contraceptives present other prescription treatments 44,45.

OTC options including active ingredients such as benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, sulphur and tea tree oil comprise the final menu of treatment options 46. The mechanism of action for these ingredients varies between preventing bacterial growth or increasing cellular turnover to encourage skin renewal. However, with the exception of tea tree oil, the use of these actives is usually limited by their irritation potential. As many consumers can attest to, overuse of these ingredients or use on sensitive skin can lead to dryness, redness and peeling. While this often limits the concentration or frequency of use of these ingredients, which in turn may impact the overall efficacy of the topical treatment, it also demonstrates the clear need for non-irritating yet effective topical acne solutions.

Cannabinoids such as CBG and CBD can fill this need as they can combat blemishes through two distinct mechanisms without irritating skin. First, CBG and CBD can inhibit inflammation caused by C. acnes as previously reported by Willow Biosciences following a study involving normal human epidermal keratinocytes 17. This complements earlier reports that cannabinoids including CBD, CBG, cannabichromene (CBC), cannabidivarin (CBDV), tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) can prevent lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in human SZ95 sebocyte cell lines 47.

Secondly, both cannabinoids can also inhibit the growth of C. acnes, with CBG being more effective than CBD 48.

These results reveal that CBG and, to a lesser extent CBD, can exert multi-functional mechanisms against the multifaceted pathogenesis of acne. As a result, cannabinoids such as CBG are extremely well positioned to tackle blemish-related issues without drying skin or compromising the skin barrier, both of which can delay the healing process and lead to post-blemish hyperpigmentation.

Interestingly (and perhaps even more promising) is the observation that the antibacterial properties of cannabinoids extend well beyond skincare. CBG has demonstrated a wide range of antibacterial effects against an array of gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens, the two broad categories most bacteria are classified into based on their cell wall composition, with bacterium that have a singular and thick peptidoglycan wall called gram-positive. Excitingly, CBG’s antibacterial effects have also been demonstrated with respect to methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a predominant culprit behind hospital acquired infections and one of the pathogens on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) watchlist for antimicrobial resistance 49-52. In addition to inhibiting the growth of this and other harmful pathogens including E. coli, CBG has been shown to inhibit and destroy bacterial biofilms, indicating potential use as a sanitiser or cleaning agent 49.

The Fifth A – Anti-Melanogenesis

Excessive production of melanin in the skin can lead to hyperpigmentation, a term used to describe uneven darker patches of skin that can be caused by everything from acne scars to sun damage. This common condition has fuelled the growth of a $6 billion skincare and treatment market. This chapter explores the recently discovered benefits of CBG for addressing hyperpigmentation and the implications this has on creating a new class of anti-melanogenesis solutions that allow for regular use without the risk of irritation while providing effective and consistent treatment.

The term “anti-melanogenesis” refers to a compound’s ability to inhibit the production of melanin, which is naturally occurring pigment produced in human skin and hair 53. Melanin is produced by cells called melanocytes, which are found in the epidermal layer of human skin 54. Skin tone is predominantly determined by the amount and type of melanin present (eumelanin as a brown and black pigments or pheomelanin as a yellow to red pigments) as well as the density of melanosomes, which are specialised cell structures that store melanin with melanocytes 55.

During a process referred to as “melanosome transfer”, melanin is transferred from melanocytes to keratinocytes 53. This process occurs as a defence mechanism against UV protection given that melanin is capable of absorbing UV radiation 53,55. This is why skin tends to darken following sunlight exposure. Despite the wonderful defence mechanism that melanin provides against UV radiation, there are several melanin-related disorders that lead to an irregular or excess production of melanin, which presents as uneven or altered skin tones and is cosmetically referred to as hyperpigmentation. Cosmetic and dermatological concerns related to hyperpigmentation are so prominent that the global pigmentation disorder market was valued at $6 billion USD in 2021 56.

A very common example is post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) which often occurs following trauma to the skin the form of blemishes, cuts, and even cosmetic treatments such as peels or light therapy 57. These traumas induce inflammation which in turn triggers localised melanin production and melanosome transfer to the site of injury 58. This results in the formation of darker spots that are often irregular in shape or size and contrasted in colour against the rest of the skin (Figure 3). While this hyperpigmentation resolves without treatment after several weeks due to the skin’s natural shedding process (also known as desquamation), in the interim these spots create an uneven skin tone and may cause psychological distress 57. UV exposure during the healing process will often exacerbate PIH and delay fading.

Figure 3: Presentation of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) associated with acne 59.

Another example of a common melanin-related disorder is age spots, otherwise known as sunspots or liver spots. As these names imply, this form of hyperpigmentation is caused by excessive and chronic sun exposure, which stimulates an overproduction and accumulation of melanin. Recent research indicates that chronic sun exposure may also impair the skin’s ability to remove melanin from the skin, further contributing to the formation of sun spots 60.

A third example includes melasma, which is characterised by patches and spots that appear darker than the natural skin tone 61. Melasma can be triggered by a range of factors, including UV exposure and hormonal changes such as those experienced during pregnancy and menopause 62. This makes melasma a particularly difficult dermatological condition to treat, as it may persist for months or years.

In response to the prevalence of pigmentation issues experienced by consumers worldwide, there are several treatments available that promise to resolve hyperpigmentation and promote an even skin tone (Table 2). However, the use and efficacy of these treatment options may be limited by their potential for skin irritation. This can manifest as redness, dryness, peeling or flaking, and in some cases, contact dermatitis or other rashes, and is of particular concern amongst consumers with sensitive skin 63. Additionally, the effectiveness of at-home treatments typically requires daily or high-frequency applications of topical products, with the concentration of active ingredient being another important factor contributing to overall efficacy. For these reasons, many skin brightening products are formulated with skin-soothing ingredients in an attempt to quell any irritation or sensitivities, but often to limited success.

Table 2: Summary of common anti-melanogenesis treatments 63-65.

Interestingly, cannabinoids present a novel solution for skin brightening remedies. Through proprietary research, Cellular Goods discovered that CBG is particularly effective for enhancing the anti-melanogenesis outcomes of select skin brightening actives. This is a promising result for 2 reasons. First and foremost, enhanced effectiveness means that a lower concentration of skin brightening active is sufficient for achieving a specific level of efficacy without the risk of irritation common to higher-strength formulas. Secondly, the pronounced anti-inflammatory properties of CBG are well suited to prevent irritation caused by common skin brightening actives. Collectively, this means that skin brightening formulations containing CBG are likely to be less irritating and better tolerated, in turn enabling frequent use and making these combinations equally (if not more effective) than standalone or conventional treatments.

Cellular Goods filed a patent based on these results and is incorporating these insights into ongoing development work. This will ensure that future formulas provide consumers with highly effective, well-tolerated and unique benefits thanks to cannabinoids such as CBG.

Conclusion

The benefits of cannabinoids for maintaining healthy skin are both far-reaching and undeniable. From ageing prevention to anti-blemish and skin brightening, cannabinoids such as CBG and CBD can provide a wide range of consumers with efficacious treatment options to address an array of skincare concerns. The multifaceted benefits of these fascinating ingredients, coupled with their well-established tolerability amongst consumers even with sensitive skin, further differentiates these compounds from many common skincare ingredients, including retinoids, Vitamin C, exfoliating acids, and benzoyl peroxide. On this basis, cannabinoids present a new class of safe and highly effective active ingredients that warrant a role in any skincare routine.

References

1. Structure and Functions of the Skin. Health and Safety Executive. Accessed August 2022. https://www.hse.gov.uk/skin/professional/causes/structure.htm.

2. Benedetti, Julia. Structure and Function of the Skin. Merck Manual (2021). Accessed August 2022. https://www.merckmanuals.com/en-ca/home/skin-disorders/biology-of-the-skin/structure-and-function-of-the-skin.

3. Pilkington, S.M., Bulfone-Paus, S., Griffiths, C.E.M., Watson, R.E.B. “Inflammaging and the Skin”. Society for Investigative Dermatology (2021). doi:10.1016/ j.jid.2020.11.006

4. Rodrigeuz-Montecino, E., Berent-Maoz, B., Dorshkind, K. “Causes, Consequences, and Reversal of Immune System Ageing”. Journal of Clinical Investigation (2013). 123(3):958-65. doi: 10.1172/JCI64096

5. Skin Care and Ageing. National Institute on Aging. Accessed August 2022. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/skin-care-and-aging

6. Del Rosso, J., Zeichner, J., Alexis, A., Cohen, D., Berson, D. “Understanding the Epidermal Barrier in Healthy and Comprised Skin: Clinically Relevant Information for the Dermatology Practitioner”. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2016). 9(4):S2-S4.

7. Ding, W., Fan, L., Tian, Y., He, C. “Study on the Protective Effects of Cosmetic Ingredients on the Skin Barrier, Based on the Expression of Barrier-Related Genes and Cytokines”. Molecular Biology Reports (2022). 49:989-995. doi:10.1007/s11033-021-06918-5.

8. Blake, A. “Cannabinoids for the Prevention of Ageing”. Cellular Goods (2022). Accessed August 2022. https://cellular-goods.com/learn/articles/research/white-paper-cannabinoids-for-the-prevention-of-aging-whitepaper

9. Newton K., Dixit, V.M. “Signaling in Innate Immunity and Inflammation”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology (2012). 4(3):a006049. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006049.

10. C., Linlin, Huidan, D., Hengmin, C., Jing, F., Zhicai, Z., Junliang, D., Yinglun, L., Xun, W., Ling, Z. "Inflammatory Responses And Inflammation-Associated Diseases In Organs". Oncotarget (2017). 9(6): 7204-7218. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23208.

11. Haque, Abid, and Heather Woolery-Lloyd. "Inflammaging In Dermatology: A New Frontier For Research". Journal Of Drugs In Dermatology (2021). 20(2):144-149. doi:10.36849/jdd.5481.

12. Zhuang, Y., John, L. "Inflammaging In Skin And Other Tissues - The Roles Of Complement System And Macrophage". Inflammation & Allergy-Drug Targets (2014). 13(3):153-161. doi:10.2174/1871528113666140522112003.

13. Lee, Y.I., Sooyeon, C., Won, S.R., Ju, H.L., Tae-Gyun, K. "Cellular Senescence And Inflammaging In The Skin Microenvironment". International Journal Of Molecular Sciences (2021). 22(8):3849. doi:10.3390/ijms22083849.

14. Chajra, H., Delaunois, S., Garandeau, D., Saint-Auret, G., Meloni, M., Jung, E., Frechet, M. "An Efficient Means To Mitigate Skin Inflammaging By Inhibition Of The NLRP3 Inflammasome And Nfkb Pathways: A Novel Epigenetic Mechanism". 30th International Federation of Societies of Cosmetic Chemists (2019).

15. Jose, S.S., Bendickova, K., Kepak, T., Krenova, Z., Fric, J. “Chronic Inflammation in Immune Ageing: Role of Pattern Recognition Receptor Crosstalk with the Telomere Complex?”. Frontiers in Immunology (2017). 8:1078. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01078.

16. Contact Dermatitis. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6173-contact-dermatitis

17. Perez, E., Fernandez, J.R., Fitzgerald, C., Rouzard, K., Tamura, M., Savile, C. “In Vitro and Clinical Evaluation of Cannabigerol (CBG) Produced via Yeast Biosynthesis: A Cannabinoid with a Broad Range of Anti-Inflammatory and Skin Health-Boosting Properties”. Molecules (2022). 27(2): 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27020491

18. Sivesind, T.E., Magfhour, J., Rietcheck, H., Kamel, K., Malik, A.S., Dellavalle, R.P. “Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions”. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Innovations (2022). 2(2). doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2022.100095.

19. Baswan, S.M., Klosner, A.E., Glynn, K., Rajgopal, A., Malik, K., Yim, S., Stern, N. “Therapeutic Potential of Cannabidiol (CBD) for Skin Health and Disorders”. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology (2020). 13:927-942. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S286411.

20. Martins, A.M., Gomes, A.L., Boas, I.V., Marto, J., Ribeiro, H.M. “Cannabis-Based Products for the Treatment of Skin Inflammatory Diseases: A Timely Review”. Pharmaceuticals (2022). 15(2):210. doi: 10.3390/ph15020210.

21. Shields, H.J., Traa, A., Van Raamsdonk, J.M. “Beneficial and Detrimental Effects of Reactive Oxygen Species on Lifespan: A Comprehensive Review of Comparative and Experimental Studies”. Frontiers in Cell Development and Biology (2021). 9:628157. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.628157.

22. Murphy, M.P. “How Mitochondria Produce Reactive Oxygen Species”. Biochemical Journal (2009). 417:1-13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386.

23. Bickers, D.R., Athar, M. “Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Skin Disease”. Journal Investigative Dermatology (2006). 126(12):2565-2575. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700340.

24. Rinnerthaler, M., Bischof, J., Streubel, M.K., Trost, A., Richter, K. "Oxidative Stress In Aging Human Skin". Biomolecules (2015). 5(2):545-589. doi:10.3390/biom5020545.

25. Briganti, S., Picardo, M. "Antioxidant Activity, Lipid Peroxidation and Skin Diseases. What's New". Journal of the European Academy Of Dermatology And Venereology (2013). 17(6): 663-669. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00751.x.

26. Liguori, I., Russo, G., Curcio, F., Bulli, G., Aran, L., Della-Morte, D., Gargiulo, G. et al. "Oxidative Stress, Aging, And Diseases". Clinical Interventions in Aging (2018). 13: 757-772. doi:10.2147/cia.s158513.

27. Atalay, S., Jarocka-Karpowicz, I., Skrzydlewska, E. “Antixoidant and Anti-inflammatory Properties of Cannabidiol”. Antioxidants (2020). 9:21. doi:10.3390/antiox9010021.

28. Kopustinskiene, D.M., Masteikova, R., Lazauskas, R., Bernatoniene, J. “Cannabis Sativa L. Bioactive Compounds and Their Protective Role in Oxidative Stress and Inflammation”. Antioxidants (2022). 11, 660. doi:10.3390/antiox11040660.

29. Bost, J., Maroon, J. “Review of the Neurological Benefits of Phytocannabinoids”. Surgical Neurology International (2018). 9:91. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_45_18.

30. Tran, J.K., Bhate, K. “A Global Perspective on the Epidemiology of Acne”. British Journal of Dermatology (2016). 172:3-12. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13462.

31. Adult Acne. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Accessed August 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne/really-acne/adult-acne

32. Acne Can Affect More Than Your Skin. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Accessed August 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne/acne-emotional-effects

33. Acne. British Skin Foundation. Accessed August 2022. https://knowyourskin.britishskinfoundation.org.uk/condition/acne/

34. Kucharska A., Szmurło, A., Sińska, B. “Significance of Diet in Treated and Untreated Acne Vulgaris”. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology (2016). 33(2):81-6. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.59146.

35. Bhate, K., Williams, H.C. “Epidemiology of Acne Vulgaris”. British Journal of Dermatology (2012). 168:474-485. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149

36. Toyoda, M., Morohashi, M. “Pathogenesis of Acne”. Medical Electron Microscopy (2001). 34(1):29-40. doi: 10.1007/s007950100002.

37. Dreno, B., Gollnick, H.P.M., Kang, S., Thiboutot, D., Bettoli, V., Torres, V., Leyden, J. “Understanding Innate Immunity and Inflammation in Acne: Implications for Management”. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (2015). 29:3-11. doi:10.1111/jdv.13190.

38. Dreno, B., Pecastaings, S., Corvec, S., Veraldi, S., Khammari, A., Roques, C. “Cutibacterium Acnes (Propionibacterium Acnes) and Acne Vulgaris: A Brief Look at the Latest Updates”. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (2018). 32:5-14. doi:10.1111/jdv.15043.

39. Leyden, J., Stein-Gold, L., Weiss, J. “Why Topical Retinoids Are Mainstay of Therapy for Acne”. Dermatology and Therapy (2017). 7(3):293-304. doi: 10.1007/s13555-017-0185-2.

40. Zaenglein, A.L., Pathy, A.L., Schlosser, B.J., Stern, M., Boyer, K.M., Bhushan, R. “Guidelines of Care for the Management of Acne Vulgaris”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2016). 74(5):945-973. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037.

41. Thielitz, A., Gollnick, H. “Topical Retinoids in Acne Vulgaris”. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (2008). 9:369-381. doi: 10.2165/0128071-200809060-00003.

42. Oral Retinoid Medicines: Revised and Simplified Pregnancy Prevention Educational Materials for Healthcare Professionals and Women. Drug Safety Update, UK Government. Accessed August 2022. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/oral-retinoid-medicines-revised-and-simplified-pregnancy-prevention-educational-materials-for-healthcare-professionals-and-women#:~:text=Women%20and%20girls%20should%20be,they%20are%20of%20childbearing%20potential.

43. Acne. Mayo Clinic. Accessed August 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/acne/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20368048#:~:text=For%20moderate%20to%20severe%20acne,macrolide%20(erythromycin%2C%20azithromycin).

44. Trivedi, M.K., Shinkai, K., Murase, J.E. “A Review of Hormone-Based Therapies to Treat Adult Acne Vulgaris in Women”. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology (2017). 44-52. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.018.

45. Słopień, R., Milewska, E., Rynio, P., Męczekalski, B. “Use of Oral Contraceptives for Management of Acne Vulgaris And Hirsutism in Women Of Reproductive and Late Reproductive Age”. Menopause Review (2018). 17(1):1-4. doi:10.5114/pm.2018.74895.

46. Decker, A., Graber, E.M. “Over-The-Counter Acne Treatments, A Review”. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2012). 5(5):32-40.

47. Oláh, A., Markovics, A., Szabó-Papp, J., Szabó, P.T., Stott,C., Zouboulis, C.C, Bíró, T. “Differential Effectiveness of Selected Non-Psychotropic Phytocannabinoids on Human Sebocyte Functions Implicates Their Introduction in Dry/Seborrhoeic Skin And Acne Treatment”. Experimental Dermatology (2016). 25(9):701-707. doi:10.1111/exd.13042.

48. Schuetz, M., Savile, C., Webb, C., Rouzard, K., Fernandez, J.R., Perez, E. “Cannabigerol: The Mother of Cannabinoids Demonstrates a Broad Spectrum of Anti-inflammatory and Anti-microbial Properties Important for Skin”. Pharmacology and Drug Development (2021). 141(5): S83. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.02.504

49. Farha, M.A. et. al. “Uncovering the Hidden Antibiotic Potential of Cannabis”. ACS Infectious Diseases (2020). 6(3):338-346. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00419.

50. Appendino, G., et. al. “Antibacterial Cannabinoids from Cannabis Sativa: A Structure-Activity Study”. Journal of Natural Products (2008). 71(8):1427-1430. doi: 10.1021/np8002673.

51. Healthcare Settings: Preventing the Spread of MRSA. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed August 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/healthcare/index.html

52. Antimicrobial Resistance. World Health Organization. Accessed August 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance

53. Kim, K., Huh, Y.J., Lim, K.M. “Anti-Pigmentary Natural Compounds and their Mode of Action”. International Journal of Molecular Sciences (2021). 22:2602. doi:10.3390/ijms22126206.

54. Schlessinger, D.I., Anoruo, M., Schlessinger, J. “ Biochemistry, Melanin”. StatPearls Publishing (2022). Accessed August 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459156/

55. Costin, G.E., Hearing, V.J. “Human Skin Pigmentation: Melanocytes Modulate Skin Color in Response to Stress”. FASEB Journal (2007). 21:976-994. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6649rev.

56. Statistics Report: Global Pigmentation Disorders Market Size and Share to Surpass USD 8.90 Billion by 2028, Predicts Zion Market Research. Cision PR Newswire (2022). Accessed August 2022. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/statistics-report-global-pigmentation-disorders-market-size--share-to-surpass-usd-8-90-billion-by-2028--predicts-zion-market-research--industry-trends-growth-value-segmentation-analysis--forecast-by-zmr-301577023.html#:~:text=Through%20the%20primary%20research%2C%20it,USD%208.90%20Billion%20by%202028.

57. Lawrence, E., Al Aboud, K.M. “Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation”. StatPearls Publishing (2022). Accessed August 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559150/

58. Maghfour, J., Olayinka, J., Hamzavi, I.H., Mohammad, T.F. “A Focused Review on the Pathophysiology of Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation”. Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research (2022). 35(3):320-327. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.13038.

59. Sangha, A.M. “Dermatological Conditions in Skin of Color—Managing Post-inflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patients with Acne”. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2021). 14(6 Suppl 1):S24-S26.

60. Choi, W., Yin, L., Smuda, C., Batzer, J., Hearing, V.J., Kolbe, L. “Molecular and Histological Characterization of Age Spots”. Journal of Experimental Dermatology (2017). 26(3):242-248. doi: 10.1111/exd.13203.

61. Melasma: Overview. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Accessed August 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/a-z/melasma-overview#:~:text=Melasma%20is%20a%20skin%20condition,diagnosis%20and%20individualized%20treatment%20plan.

62. Melasma. British Skin Foundation. Accessed August 2022. https://knowyourskin.britishskinfoundation.org.uk/condition/melasma/#:~:text=The%20exact%20cause%20is%20not,control%20pills%20and%20hormone%20replacement.

63. Nautiyal, A., Wairkir, S. “Management of Hyperpigmenation: Current Treatments and Emerging Therapies”. Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research (2021). 34(6):1000-1014. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12986

64. Davis, E.C., Callender, V.D. “Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation: A Review of the Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Treatment Options in Skin of Color”. The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2010). 3(7):20-31.

65. Arora, P., Sarkar, R., Garg, V.K., Arya, L. “Lasers for Treatment of Melasma and Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation”. Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery (2012). 5(2):93-103. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.99436.